From the Garden of Poets to the Epic Plain

Leaving the rose-scented gardens of Nishapur, the journey toward Tus feels less like a change of place than a shift in register. Where Khayyam measured the instant and Attar invited the soul to descend inward, Ferdowsi calls us to stand upright before the long duration of history. The horizon unfurls, broader and more austere, as if preparing the mind for an epic scale. In this stretch of Khorasan, silence thickens; it no longer whispers metaphysics, it bears memory.

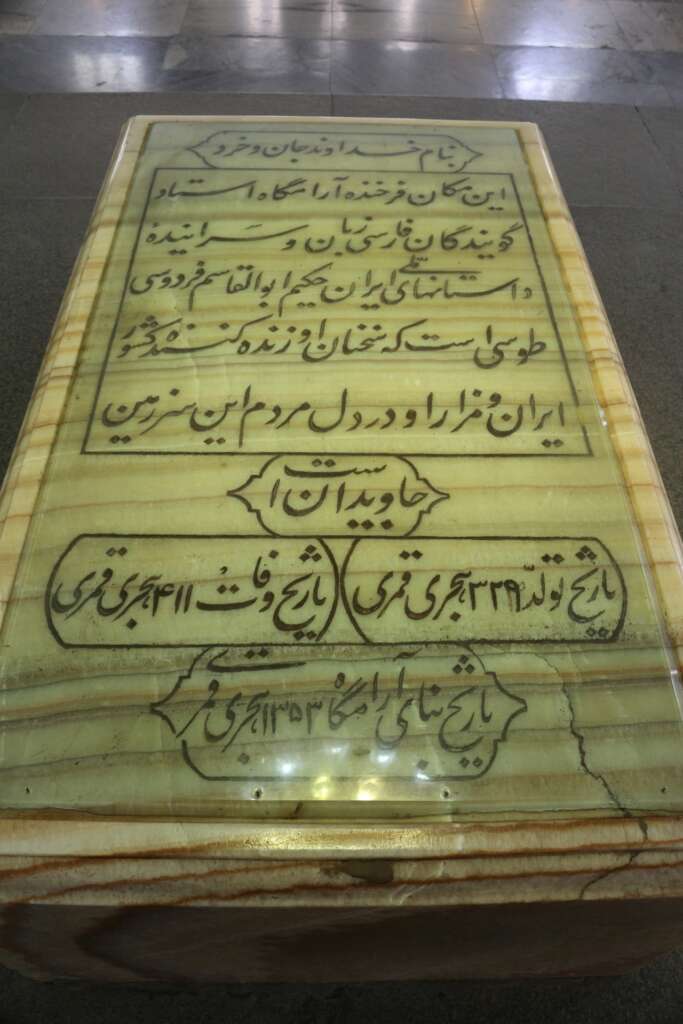

The mausoleum of Ferdowsi emerges calmly within its gardens, surrounded by water and trees, inhabited by ordinary gestures—families strolling, children leaning over fountains. Life does not interrupt the epic here; it confirms it. Ferdowsi wrote the Shâh Nâmeh to save a language and a memory from erasure, and standing before his tomb, one senses that this labor was not aimed at glory but at continuity.

“Much I suffered through these thirty years, to give life again to Persia through the word.”

The monument does not rise in triumph; it holds its ground, like a sentence patiently completed.

Rostam: Strength Without Knowledge

Among all the figures of the Shâh Nâmeh, it is Rostam who inhabits this place most fully. Not as a victorious hero, but as a burdened one. Rostam is strength without clarity, courage bound to a tragic blindness—a figure whose greatness lies precisely in his tragic limits. Walking past the stone reliefs, where battles are frozen in restrained gestures, I felt that the epic here does not celebrate force, but questions it. Ferdowsi’s voice is unwavering:

“You are mighty in arm, yet fate is mightier than you.”

The story of Rostam and Sohrab unfolds like a wound at the heart of the epic. Father and son meet as enemies, unaware of the bond that unites them. When recognition finally comes, it arrives too late, and Ferdowsi gives voice to a grief that transcends time:

“If wisdom had ruled instead of fate, this deed would not have been done.”

In Tus, this line feels carved not only in stone, but in air. The tragedy is not caused by hatred, but by ignorance—by the fatal separation of power from knowledge. Here, the epic becomes ethical meditation, reminding us that strength, when unaccompanied by insight, turns against itself.

The Fall of the Hero and the Survival of the Word

Rostam’s end is neither heroic nor luminous. Betrayed, trapped in a pit dug by those he trusted, he falls not to an enemy, but to treachery. Ferdowsi narrates this fall with sober restraint, concluding with a line that resonates deeply at his tomb:

“Thus passes the mighty one; only the word remains.”

Standing there, I understood that this sentence is the true architecture of the Shâh Nâmeh. Empires crumble, heroes disappear, bodies return to dust—but language endures as a vessel of memory. At the threshold of Ferdowsi’s resting place, the journey through Khorasan found its epic counterpart. From the geometry of Khayyam to the inward talisman of Attar, and now to the long breath of the Shâh Nâmeh, each station revealed a different relationship to time.

Final Reflections on the Road

Tus teaches endurance—not as resistance, but as transmission. In the quiet flow of water and the steady presence of stone, the epic continues—as enduring as the turquoise of Nishapur, a vigilant reminder that what saves a people is not power, but the care with which it remembers itself.